For more than a decade, I’ve been ending talks by looking forward to the rich data that will soon begin flowing from the Vera Rubin Observatory. The observatory’s magnificent new telescope, nearing its long-awaited first light on a mountaintop in Chile, will conduct a ten year survey of the sky, producing 30 TB of images and maybe ten million alerts a night, covering everything from asteroids to distant galaxies.

The Observatory has – from really early on – seen citizen science, and in particular working with the Zooniverse, as an important part of how they intend to make the most of this firehose of data. We’ve been working hard on things like making data easy to transfer across, designing tools for helping scientists building good projects and more.

All of which is to say I’m very excited – as a Zooniverse person, and as an astronomer – about the opportunities ahead. To allow time for me to concentrate on making the most of it – and in particular, in learning how to find odd stuff alongside Zooniverse volunteers – I’ve decided it’s time for me to step down as Zooniverse Principal Investigator, a position I’ve held since…well, since before the Zooniverse existed.

After 15 or so years, it’s well past time for other people to lead. Laura Trouille from the Adler Planetarium has been my co-PI since 2015, and will be taking over as Principal Investigator. Laura is brilliant, and has been the driving force behind much of what we’ve been doing for a long time. I’m confident in her, and along with her fabulous team, I’m excited to see where she leads this marvellous platform and project. With a growing partnership with NASA, new ideas in how to use Zooniverse in education and reaching new communities, and – of course – new projects launching each week, I genuinely think that we’re in a strong place to keep allowing everyone to participate in science.

In terms of stepping down from this role, I’ll be more Joe Root than Stuart Broad (Note to Americans: This is a cricket reference) – there is a long-standing ‘joke’ that no-one actually leaves the Zooniverse – sticking around the team to serve as Senior Scientist, giving advice where needed and continuing to lead specific projects and efforts. The team in Oxford will work more closely than ever with the rest of the collaboration, and our plans for Rubin and the Zooniverse will be unaffected.

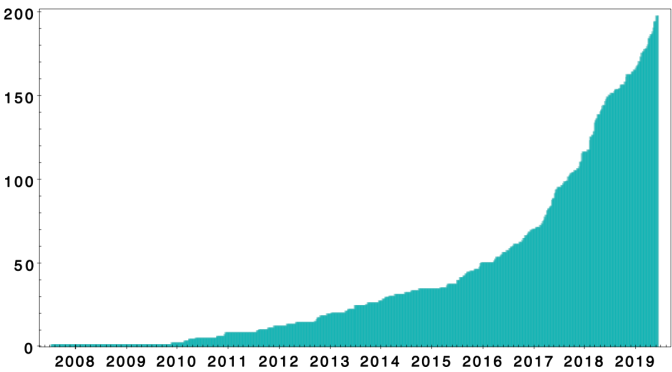

It is, however, strange to be contemplating a change after all this time. I’m immensely proud of the fact that once we stumbled onto the success of the original Galaxy Zoo (a story told in a very reasonably priced book…), we had the imagination not just to build another Galaxy Zoo (which we did – classifications still needed!) but a platform that covers such a wide variety of fields, and through which volunteers have contributed three-quarters of a BILLION classifications. Thanks to the support of all manner of organizations, I’m also very proud that we haven’t had to charge researchers for access to the Zooniverse; the only criteria that have ever mattered has been whether a project will contribute to science and be welcomed by our volunteers.

I’m so grateful to those who have lent their effort, energy and expertise to making a Zooniverse which is grander than I would ever have dared on my own. In particular: Arfon Smith, who created the original Zooniverse with me and took over from me as Director of Citizen Science at Adler, and Lucy Fortson, who has been the best grant-writer and collaborator I could wish for as well as putting up with my stresses more than anyone should have to. I’ll stop here, else I’ll end up listing all of the developers, researchers and volunteers who have made this unique project what it is.

Onwards! Let us make, and set the weather fair.

See you in the Zooniverse.

September 2023