This is a guest post by summer intern Anastasia Unitt.

The study of celestial objects creates a huge amount of data. So much data, that astronomers struggle to make use of it all. The solution? Citizen scientists, who lend their brainpower to analyse and catalogue vast swathes of information. Alex Andersson, a DPhil student at the University of Oxford, has been applying this approach to his field: radio astronomy, through the Zooniverse. I met with him via Zoom to learn about his project detecting rare, potentially explosive events happening far out in space.

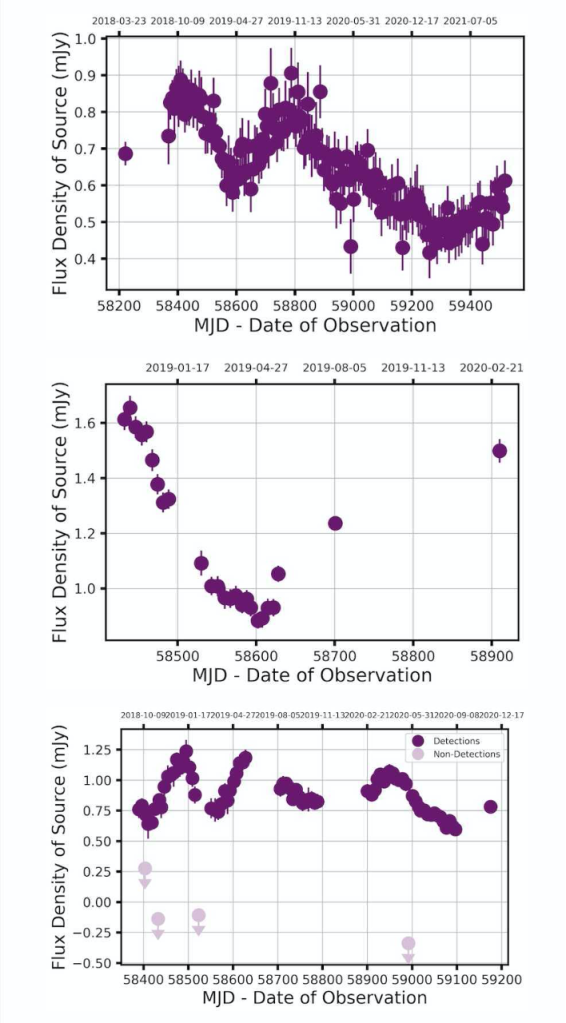

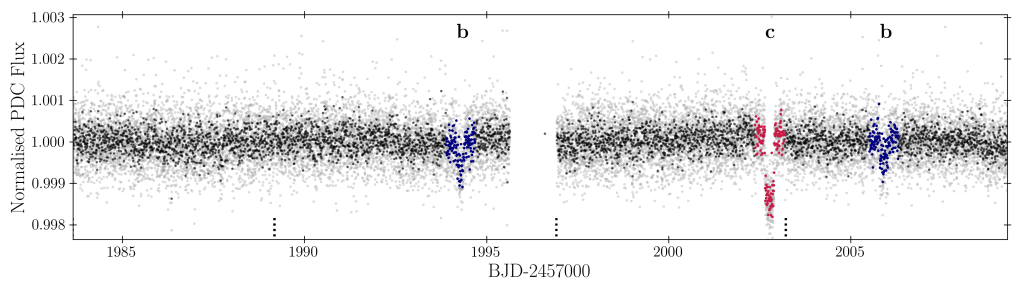

Alex’s research uses data collected by a radio telescope located thousands of miles away in South Africa, named MeerKAT. The enormous dishes of the telescope detect radio waves, captured from patches of sky about twice the size of the full Moon. This data is then converted into images, which show the source of the waves, and into light curves, a kind of scatter plot which depicts how the brightness of these objects has changed over time. This information was initially collected for a different project, so Alex is exploiting the remaining information in the background- or, as he calls it: “squeezing science out of the rest of the picture.” The goal: to identify transient sources in the images, things that are changing, disappearing and appearing.

Historically, relatively few of these transients have been identified, but the many extra pairs of eyes contributed by citizen scientists has changed the game. The volume of data analysed can be much larger, the process far faster. Alex is clearly both proud of and extremely grateful to his flock of amateur astronomers. “My scientists are able to find things that using traditional methods we just wouldn’t have been able to find, [things] we would have missed.” The project is ongoing, but his favourite finding so far took the form of a “blip” his citizen scientists noticed in just two of the images (out of thousands). Alex explains: “We followed it up and it turns out it’s this star that’s 10 times further away than our nearest stellar neighbor, and it’s flaring. No one’s ever seen it with a radio telescope before.” His excitement is obvious, and justified. This is just one of many findings that may be previously unidentified stars, or even other kinds of celestial objects such as black holes. There’s still so much to find out, the possibilities are almost endless.

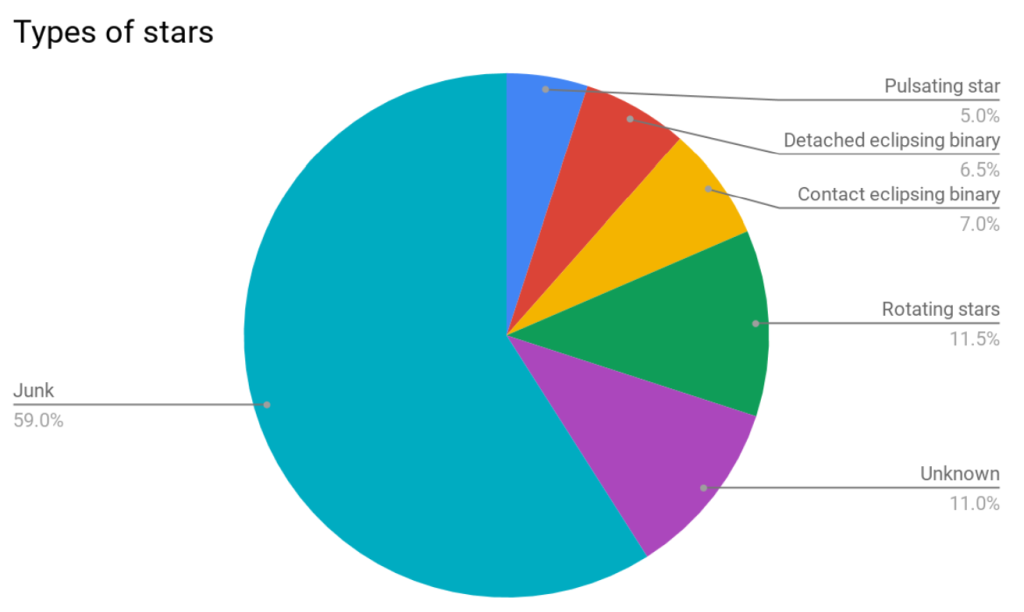

A range of light curve shapes spotted by Zooniverse citizen scientists performing classifications for Bursts from Space: MeerKAT

Unfortunately, research comes with its fair share of frustrating moments along with the successes. For Alex, it’s the process of preparing the data for analysis which has proved the most irksome. “Sometimes there’s bits in the process that take a long time, particularly messing with code. There can be so much effort that went into this one little bit, that even if you did put it in a paper is only one sentence.” These behind-the-scenes struggles are essential to make the data presentable to the citizen scientists in the first place, as well as to deal with the thousands of responses which come out the other side. He assures me it’s all worth it in the end.

As to where this research is headed next, Alex says the prospects are very exciting. Now they have a large bank of images that have been analysed by the citizen scientists, he can apply this information to train machine learning algorithms to perform similar detection of interesting transient sources. This next step will allow him to see “how we can harness these new techniques to apply them to radio astronomy – which again, is a completely novel thing.”

Alex is clearly looking forward to these further leaps into the unknown. “The PhD has been a real journey into lots of things that I don’t know, which is exciting. That’s really fun in and of itself.” However, when I ask him what his favourite part of this research has been so far, it isn’t the science. It’s the citizen scientists. He interacts with them directly through chat boards on the Zooniverse site, discussing findings and answering questions. Alex describes their enthusiasm as infectious – “We’re all excited about this unknown frontier together, and that has been really, really lovely.” He’s already busy preparing more data for the volunteers to examine, and who knows what they might find; they still have plenty of sky to explore.