In this edition of Who’s who in the Zoo, meet Marianne Barrier, who is part of the Monkey Health Explorer team.

Who: Marianne Barrier, Lab Manager, Genomics & Microbiology Research Lab

Location: North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, NC, USA

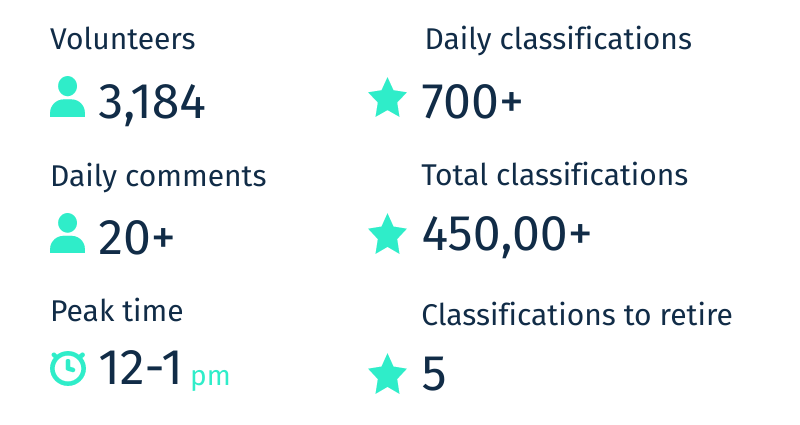

Zooniverse project: Monkey Health Explorer

What is your research about?

I’m actually trained in genetics and using DNA as a tool, so I’ve had to expand my knowledge to other areas as we set up our Monkey Health Explorer project. This project is one piece of a larger puzzle being assembled by a collaborative group of scientists all studying different aspects of a colony of Rhesus macaque monkeys living on an island off the coast of Puerto Rico. Our piece involves examining the blood of these monkeys to get a snapshot of their health, just like when we have our blood drawn at a doctor’s office. The data we collect about the blood cells is then examined alongside data from other researchers, such as behavioral or gene expression data, to tell more about each monkey.

How do Zooniverse volunteers contribute to your research?

The primary focus of our project is to count the 5 types of white blood cells in blood smears in order to determine if these numbers are in the “normal” ranges for a healthy monkey or if they might indicate the monkey is sick. Our volunteers learn about the visual features of each type of white blood cell and contribute to our research by identifying the white blood cells in blood smear images from our monkeys. We then summarize the results from all volunteers to give us the white blood cell counts for each monkey sample.

In addition to helping us identify these cells, we have several volunteers who are trained cell professionals or medical or veterinary students who have given us additional insights into our monkeys. They have pointed out unique patterns in the cells that indicate specific illnesses, such as parasitic infections.

What’s a surprising or fun fact about your research field?

Rhesus macaque blood cells look very similar to human blood cells. I learned how to identify the cells in our project using training materials for human blood.

The “positive” and “negative” part of our blood types is called the “Rh factor” because that particular type of blood protein was first identified in Rhesus macaque monkeys.

What first got you interested in research?

I’ve always loved learning how things work and was a big fan of the TV show MacGyver because he could figure out how to resolve a problem by using items he had around him. This inspired me to think about how to approach a problem from multiple views and come up with potential solutions using standard and non-standard methods.

What’s something people might not expect about your job or daily routine?

The lab I work in is inside of a Museum and has glass walls, so visitors can watch us work. Sometimes when I step outside the lab, I end up talking with visitors about what we’re doing and answering their questions about what they can see, such as our DNA sequencers and liquid handling robot. We also have special events at the Museum where I have the opportunity to share about our Monkey Health Explorer project to visitors and also host teacher training workshops to show them how to incorporate our project into their classroom with the educational materials we’ve developed.

Outside of work, what do you enjoy doing?

My love of learning extends to everything – I read/listen to audiobooks (mysteries lately), have 3 languages going on Duolingo (French, Spanish, German), rotate between crafty hobbies (painting, drawing, knitting, 3D print design), play multiple instruments (learning drums now), and recently added 2 bee hives to our garden.

What are you favourite citizen science projects?

I do love adding photos to iNaturalist as I come across new (to me) creatures and plants as I explore outside.

What guidance would you give to other researchers considering creating a citizen research project?

I would suggest spending time exploring several projects that have similarities to what you’re thinking of designing and use these as guides to consider what type of information you want to get from your project and how best to design training to make it interesting and accessible to volunteers. Also, make use of the Zooniverse Talk to interact with other project researchers to gain insights and learn from them. It’s a great community with a wealth of knowledge and experience!