This guest post was written by the Davy Notebooks Project research team. It was updated on 21 October 2024 to include a link to the published transcription site.

The Davy Notebooks Project first launched as a pilot project in 2019. After securing additional funding and three months of testing and revision, the project re-launched in June 2021 in its current, ‘full’ iteration. And now it is drawing to a close.

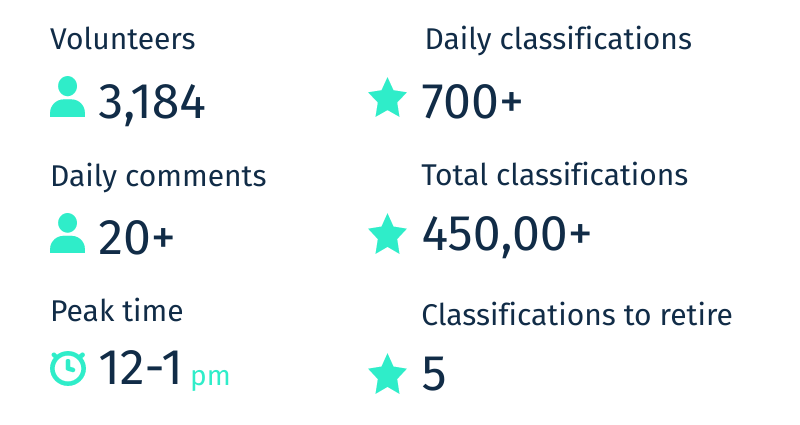

Since April 2021, 11,991 pages of Davy’s manuscript notebooks have been transcribed – this, of course, is a major achievement. Adding the 1,130 pages transcribed during our pilot project, which launched in April 2019, brings the total up to 13,121 pages. Including Zooniverse beta test periods (during which time relatively few pages were made available to transcribe), this was achieved in a period of forty-one months; discounting beta test periods brings the total down to thirty-six months. At the time of writing, with the transcription of Davy’s 129 notebooks now complete, the Davy Notebooks Project has 3,649 volunteers from all over the world. 505 volunteers transcribed during our pilot project, so the full project attracted 3,144 transcribers.

The transition from the pilot build to the developed full project that, at its peak, was collecting up to 6,675 individual classifications per month, has been a steady learning experience. Samantha Blickhan’s article (co-authored by other members of the project team) in our special issue of Notes and Records of the Royal Society, ‘The Benefits of “Slow” Development: Towards a Best Practice for Sustainable Technical Infrastructure Through the Davy Notebooks Project’, charts the Davy Notebooks Project’s development, and makes a convincing case for the type of ‘slow’ development – or gradual improvement in response to feedback – approach that the project has taken.

While new notebooks were being released and transcribed on Zooniverse, the project’s editorial team were reviewing and editing the submitted transcriptions through Zooniverse’s ALICE (Aggregated Line Inspector and Collaborative Editor) app. The team were also engaging, daily, with our transcriber community on the project’s Talk boards – discussing particularly tricky or interesting passages in recently transcribed pages, sharing information and insights on the material being transcribed, and creating a repository of useful research that has been valuable in tracing connections throughout Davy’s textual corpus as a whole and in writing explanatory notes for the transcriptions. The current number of individual notes (repeated throughout the edition as necessary) stands at approximately 4,500.

Running a successful online crowdsourcing project requires effective two-way communication between the project team and the volunteer community. A series of ‘off Zooniverse’ volunteer-focused events offered the opportunity to engage with our volunteers, and – importantly – a venue to thank them for their continued, frequently excellent efforts in transcribing and interpreting Davy’s notebooks. Conference panels at large UK conferences with international representation (the British Society for Literature and Science conferences in 2022 and 2023, the British Association for Romantic Studies conference, jointly held with the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism, in 2022) enabled the project team to share their research-in-progress with the academic community, and our own conference, ‘Science and/or Poetry: Interdisciplinarity in Notebooks’, held at Lancaster University in July 2023, brought together scholars working on a diverse range of notebooks and other related manuscript materials to share our most recent insights and findings. Our monthly project team reading group, superbly organised by Sara Cole over several years, helped us to think about the organisation of Davy’s notebook collection as a whole, and created many a new research lead. Our travelling exhibition, which stopped at the Royal Institution, Northumberland County Hall, and Wordsworth Grasmere, has created new interest in Davy and his notebooks, and presented some of the key research findings of the project. All of these events fed directly into maintaining the momentum of the Davy Notebooks Project.

We are now moving towards the publication of the free-to-access digital edition of Davy’s whole notebook corpus that has been our goal since the start. Our digital edition will be hosted on the Lancaster Digital Collections platform, which is based on the well-established Cambridge Digital Library platform. View the Davy Notebooks transcription collection here: https://digitalcollections.lancaster.ac.uk/collections/davy/1.

Thankfully, we have benefited from the continued involvement, post-transcription, of a core of volunteer transcribers, who have taken on new responsibilities in assisting with the final editing of the notebooks; special thanks go to David Hardy (@deehar) and Thomas Schmidt (@plphy), who have helped to improve our transcriptions and notes in significant measure. We have also benefited at various points in the project from additional research assistance, from our UCL STS Summer Studentship project interns (Alexander Theo Giesen, Mandy Huynh, Stella Liu, Clara Ng, and Shreya Rana), from specialists in early nineteenth-century mathematics (Brigitte Stenhouse and Nicolas Michel), and from students and postgraduates in the Department of English Literature and Creative Writing at Lancaster University (Emma Hansen, Lee Hansen, Rebekah Musk, Frank Pearson, and Rebecca Spence), for which we are very grateful.

Work continues behind the scenes on finalising the transcriptions on LDC, and on the preparation of our forthcoming special issue of Notes and Records of the Royal Society, which is due to be published at the end of the year. Our digital edition will be officially launched at Lancaster Litfest on Saturday 19 October 2024. This will give us another opportunity to thank the thousands of volunteers who have made this work possible.

Truly, we could not have made the important advances in Davy scholarship that we have made since 2019 without every one of our volunteers, who gave freely and generously of their time and knowledge, and who hopefully enjoyed playing such a key role in a large research project – this is not only a social edition of Davy’s notebooks, but also, in large measure, their edition. Thank you all.