What are “Yellowballs?” Shortly after the Milky Way Project (MWP) was launched in December 2010, volunteers began using the discussion board to inquire about small, roundish “yellow” features they identified in infrared images acquired by the Spitzer Space Telescope. These images use a blue-green-red color scheme to represent light at three infrared wavelengths that are invisible to our eyes. The (unanticipated) distinctive appearance of these objects comes from their similar brightness and extent at two of these wavelengths: 8 microns, displayed in green, and 24 microns, displayed in red. The yellow color is produced where green and red overlap in these digital images. Our early research to answer the volunteers’ question, “What are these `yellow balls’?” suggested that they are produced by young stars as they heat the surrounding gas and dust from which they were born. The figure below shows the appearance of a typical yellowball (or YB) in a MWP image. In 2016, the MWP was relaunched with a new interface that included a tool that let users identify and measure the sizes of YBs. Since YBs were first discovered, over 20,000 volunteers contributed to their identification, and by 2017, volunteers catalogued more than 6,000 YBs across roughly 300 square degrees of the Milky Way.

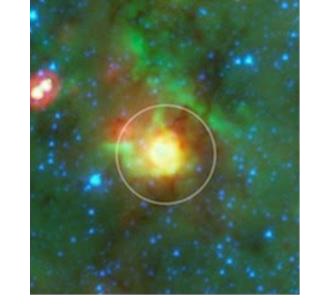

New star-forming regions. We’ve conducted a pilot study of 516 of these YBs that lie in a 20-square-degree region of the Milky Way, which we chose for its overlap with other large surveys and catalogs. Our pilot study has shown that the majority of YBs are associated with protoclusters – clusters of very young stars that are about a light-year in extent (less than the average distance between mature stars.) Stars in protoclusters are still in the process of growing by gravitationally accumulating gas from their birth environments. YBs that represent new detections of star-forming regions in a 6-square-degree subset of our pilot region are circled in the two-color (8 microns: green, 24 microns: red) image shown below. YBs present a “snapshot” of developing protoclusters across a wide range of stellar masses and brightness. Our pilot study results indicate a majority of YBs are associated with protoclusters that will form stars less than ten times the mass of the Sun.

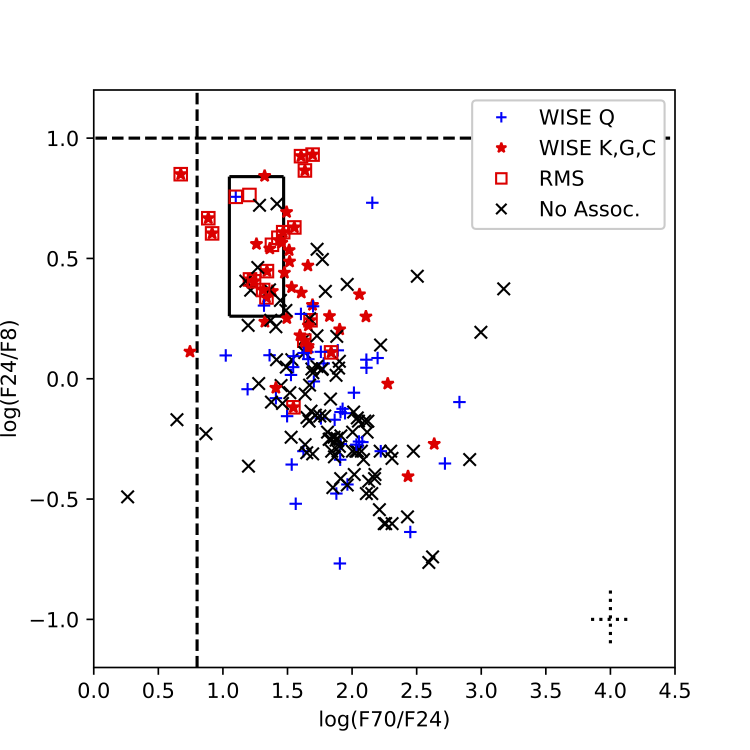

YBs show unique “color” trends. The ratio of an object’s brightness at different wavelengths (or what astronomers call an object’s “color”) can tell us a lot about the object’s physical properties. We developed a semi-automated tool that enabled us to conduct photometry (measure the brightness) of YBs at different wavelengths. One interesting feature of the new YBs is that their infrared colors tend to be different from the infrared colors of YBs that have counterparts in catalogs of massive star formation (including stars more than ten times as massive as the Sun). If this preliminary result holds up for the full YB catalog, it could give us direct insight into differences between environments that do and don’t produce massive stars. We would like to understand these differences because massive stars eventually explode as supernovae that seed their environments with heavy elements. There’s a lot of evidence that our Solar System formed in the company of massive stars.

The figure below shows a “color-color plot” taken from our forthcoming publication. This figure plots the ratios of total brightness at different wavelengths (24 to 8 microns vs. 70 to 24 microns) using a logarithmic scale. Astronomers use these color-color plots to explore how stars’ colors separate based on their physical properties. This color-color plot shows that some of our YBs are associated with massive stars; these YBs are indicated in red. However, a large population of our YBs, indicated in black, are not associated with any previously studied object. These objects are generally in the lower right part of our color-color plot, indicating that they are less massive and cooler then the objects in the upper left. This implies there is a large number of previously unstudied star-forming regions that have been discovered by MWP volunteers. Expanding our pilot region to the full catalog of more than 6,000 YBs will allow us to better determine the physical properties of these new star-forming regions.

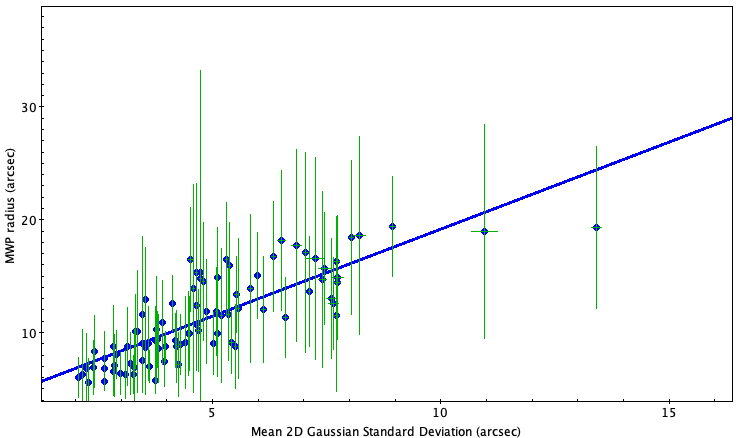

Volunteers did a great job measuring YB sizes! MWP volunteers used a circular tool to measure the sizes of YBs. To assess how closely user measurements reflect the actual extent of the infrared emission from the YBs, we compared the user measurements to a 2D model that enabled us to quantify the sizes of YBs. The figure below compares the sizes measured by users to the results of the model for YBs that best fit the model. It indicates a very good correlation between these two measurements. The vertical green lines show the deviations in individual measurements from the average. This illustrates the “power of the crowd” – on average, volunteers did a great job measuring YB sizes!

Stay tuned… Our next step is to extend our analysis to the entire YB catalog, which contains more than 6,000 YBs spanning the Milky Way. To do this, we are in the process of adapting our photometry tool to make it more user-friendly and allow astronomy students and possibly even citizen scientists to help us rapidly complete photometry on the entire dataset.

Our pilot study was recently accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal. Our early results on YBs were also presented in the Astrophysical Journal, and in an article in Frontiers for Young Minds, a journal for children and teens.