Today’s guest post comes from Sarah Xu and Thomas Janopoulos about their experience as our Citizen Science interns at the Adler Planetarium as part of the Teen Intern Program.

Sarah Xu is currently a senior attending Air Force Academy High School. She has a wide range of interests that change all the time, but computer science has been an interest ever since she was introduced to it in 7th grade. She also is really into Biology, but the Adler Planetarium has recently sparked interests in Astronomy.

Thomas (Tommy) Janopoulos is a Sophomore at Jones College Preparatory High School. He aspires to be an aerospace engineer, focusing on the mechanical engineering aspects of the field. He has a large interest in using the autodesk inventor program, a 3D modeling program to recreate objects virtually.

How did you become a Teen Intern at Adler Planetarium?

Tommy: I learned about the Adler teen internship from my sister, who was a long time volunteer at the Adler. She suggested that I apply to their upcoming internship. She explained that I already know some of the staff from the Web Making for Civic Hacking program, which was a program where we created websites about teen issues to present to problem solvers interested in finding solutions to our issues, we did earlier in the year and having a familiarity with the staff would make the transition into a work environment easier. Also the fact that the Adler is a space science museum would be great for me considering I want to go into aerospace engineering as a profession. So I decided to apply to the internship and now I am in the Citizen Science intern position creating an activity on a Zooniverse project about urban wildlife in Chicago.

Sarah: How I got my internship has a lot to do with my school. Air Force Academy High School has a partnership with Adler. Freshmen year, we had several field trips where we did various activities around the Adler. Many of the students at my school get involve with the Adler. I was brought into the a teen program, Youth Leadership Council (YLC), my sophomore year by one of the volunteers who attended my school. Youth Leadership Council is an after school program where teens plan workshops for civic hack day, a day where people come to offer solutions for any problems that are presented. There I got to know Nathalie Rayter, who is in charge of the Adler teen programs and internship. By talking to her, I received a lot of opportunities to be part of the planetarium. Junior year, I was a member of YLC and a volunteer telescope facilitator. I just kept coming back to Adler through many different programs. This summer I was looking for something to do because I previously interned at an investment firm, but didn’t really enjoyed it much. I was trying to find an internship that’ll provide a different experience. My classmates and teachers along with Nathalie told me to go for the Adler internship. I applied and got the position as a Citizen Science Intern!

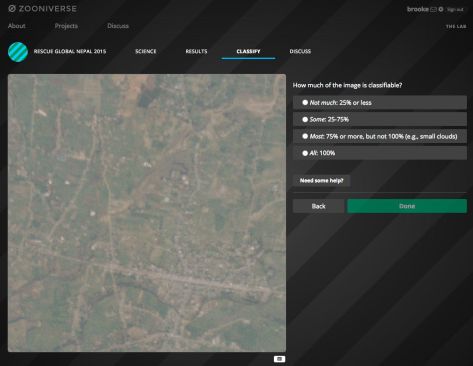

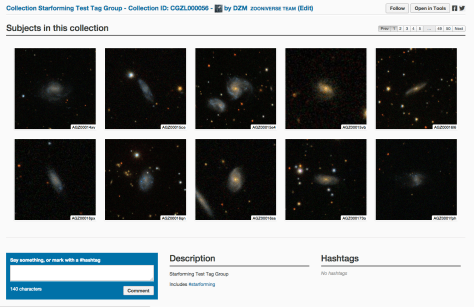

As a citizen science intern, I learned a lot of what the Zooniverse does. Zooniverse is a group of people who work on websites for citizen science. On my first day, I was introduced to two projects. One of them is finished while the other one is still being worked on, but will launch September 10th. Tommy, my peer, and I chose to work with the one that is still being worked on. The reason for that is it takes place in Chicago and it would be a bit easier to have the participants we meet at events around Chicago connect to it. Our project with our department is to design an interactive activity that will spread the word of this citizen science project and also citizen science itself. We designed our activity for mainly museum visitors, such as families and younger kids.

What does being a Teen Intern entail?

A teenager as an intern… the title says it all! A bunch of teenagers working together sounds like a lot of fun. For the most part it is, but it also requires many skills to become one. As teen interns at the Adler Planetarium, we have several projects going on. Every intern is assigned to a department with a supervisor who will give you projects to accomplish. On top of that, every teen is required to work on a personal project that we have to pick from a list. Every teen has to make a project to be showed off at the Community Bash which is a party to display what we have done over the summer. We also have to do our daily jobs which can consist of various tasks such as making an activity to being on the floor doing an activity. Now it might not be something that is interesting to you, but having an open mind is very important. You never know until you actually follow through with the project and that is from personal experience! With all these projects happening all within the same 8 weeks, we have to be very organized and on top of our schedule in order to finish them in time. One badly organized and managed day will set everything behind! But incase that does happen, communication and diligence were the key things that helped put us back on track. It is imperative to communicate with our supervisors and other peers so that we can collaborate to get our work done. This internship is not about working alone at all. 99% of the time we did activities and projects with each other. You must be able to work with others because that will really help you succeed in this internship. There is just one last thing you need… Enthusiasm! You will be interacting with lots of visitors and your peers. If you do not have a positive attitude everything else you need to succeed in this internship will not be able to flow because no one wants to work with someone that does not want to be there.

How did you choose what to work on and what did you need to learn to do the work?

When we walked into Zooniverse, Julie, our supervisor, gave us a run through of what citizen science is and what kind of work they do in the office. Then she told us about the two newest biology projects: Condor Watch and a project looking at urban wildlife in Chicago (now with a name, Chicago Wildlife Watch). Condor Watch is up and running, while the other project launches September 10th. Fortunately with the launch date near, they had a demo site we were able to explore to get a feel of what it is. So, we played around with the projects to see what they’re really about. We were given the option to either work together on one or separately on either. Tommy said he liked the animal conservation one because it takes place in Chicago and I agreed. We figured it was easier to introduce the activity and connect it with most of the museum visitors because we’re in Chicago. It’s also a good way for Chicagoans to be more aware of what’s truly around them in this amazing city. It is not just buildings and artifacts; we also have nature that could put people in awe as well.

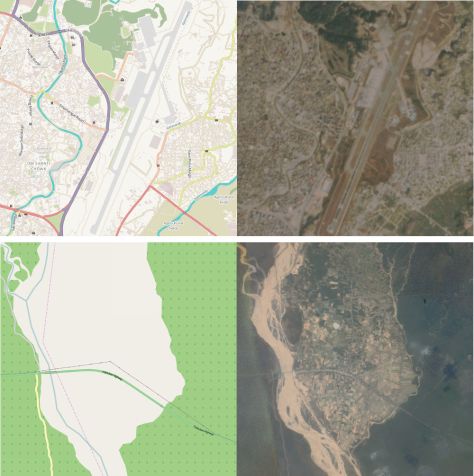

Chicago Wildlife Watch is a collaboration between the Urban Wildlife Institute at Lincoln Park Zoo partnered with Zooniverse to create a project that will help with animal conservation in Chicago. Camera traps are set up all around Chicago to gather images of what kind of animals live here, their behavior, and how they interact in the urban setting. So we came up with an activity that will not only help promote the project, but also convey the message of nature being everywhere to the public. We designed this activity with museum visitors in mind, meaning it is aimed towards younger kids and families. We use animal cards containing the picture and some factoids of the animals along with a big image of a basic background with a house, park, tree, underground, and water. During the activity, depending on the age group, we give the physical description of the animal and have the kids guess it, whereas with little kids, we would show them the picture and have them guess that way. If they guessed it right, we would hand them the card and have them stick it up to where they think the animal lives. Even though we live in the urban Chicago, we’re still part of nature. Along with that, we hope that participants will have an idea of what citizen science is and what exactly is Zooniverse. A more detailed description and run through will be up on Zooteach when the project launches on September 10th!

After we chose what project we wanted to make an activity around, we had to first learn what concepts we would need to cover, so we went onto the demo site to learn more about the project. We had to researched what conservation is and how it applies to the project so we could have a better understanding on what points we wanted to get across for our participants. Looking at the website and the background information given wasn’t enough. We had a meeting with one of the driving forces of the project, Seth, and one of the lead members of the Lincoln Park Zoo and its Urban Wildlife Institute on what he would like people to take away from our activity. He said, “I want people to know that nature is everywhere”. That gave us a way to go on our activity. It was hard to come up with an activity to do. We tried to google some classroom activities that teachers do for animal conservation. After a few days of research and talking to our supervisor, we took a whole morning to just brainstorm outreach activity ideas. Our supervisor gave us an activity idea earlier that week on how they had classrooms work to classify images of animals and put them into the according bin or bag. So then we took that idea and try to add on to it to fit into our urban wildlife activity. We thought we could have people classify the animals of Chicago. Then we came up with an idea of having our participants try to guess what animals live in Chicago since the project looks at Chicago’s urban wildlife. We thought this activity would hit our learning goal of understanding what nature is and that it is all around us, even in the city. So we presented this idea to our supervisor and then ran with it. We typed up our concept and showed it to peers and supervisors and were constantly updating and adjusting to develop the best activity possible. Now time to test it out!

Our visit to the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum helped us to a realize what age group we really aim for. At the Nature Museum, there was mostly little kids who are around 3 or 4 years old excluding summer camps. We weren’t able to test it with kids that young because there is a limited amount of knowledge as to what the kids know about urban wildlife. They do know the very basic animals, but it was hard to carry out our whole activity because our activity contains questions that are at elementary school level. However, there were adults that were interested in what we do and often they are parents of little kids. With the adults, we found out that we just have to describe what citizen science is, what the Zooniverse does, and the project that they’re currently working on. We would proceed to do the end part of our activity which is to show them the demo site of Chicago Wildlife Watch. They would try out the demo site and because it only has a limited amount of pictures, we would try to direct them to try out our other projects. Sometimes Snapshot Serengeti would be used to show a better demonstration of what the fully functional website of the project would look like. At the end of the talk, either one of us would give them a postcard to encourage the visitors to go on Zooniverse.org to try out the projects on there. Through testing it on the floor at Adler, we noticed that it is difficult to draw people in. Creativity really helps with floor activities. People are usually more drawn into something “cool”.

What were the challenges with your project?

Sarah: After we designed the activity, we had to test it out on the floor. That was the second most challenging part of the whole project. The first was having to come up with an activity that’s will get people involved and convey the message we want. I’ve always struggled with public speaking. It was hard for me to go up to the visitors and ask them to help us test run the activity. However, I got past the awkward stage after having to interact with visitors on so many different occasions.

Tommy: Creating this activity has been so much fun and enjoyable but like any other job it had its challenges. My biggest challenge was taking a Citizen Science project and creating a fun interactive activity that educates people about urban wildlife and how they can contribute to science. When you get this job of creating an activity you think creating an activity is easy but having to consider how people learn, how not to bore young kids, how to get people to stop and participate, and how to hit all of your objectives you set becomes a massive task. With a lot of hard work and the help of my peer Sarah, we researched and brainstormed and found a way to take all of these aspects into one activity which is now “What Lives With Us.”

What do you feel you have gained from being a Teen Intern this summer?

Sarah: Through this internship, I had to talk to visitors a lot, so communications and public speaking are things that I got away from it. My ways of starting a conversation and demonstrating things to the public has improved. Aside from that, I was also able to learn what Zooniverse does, what citizen science is, and about Chicago’s wildlife. More importantly, I’ve gained friendships with other teens and professional relationships with the staff members that will only benefit me. It’s great to be able to have this experience of interning at a museum. This summer has been awesome thanks to the Adler, and I hope all the other teens and supervisors had as much fun as I did!

Tommy: This internship has given me so much its hard to put it into one sentence but the one thing I can say is that this job is incomparable to any other opportunity for someone my age. This gives teenagers the opportunity to gain work experience and actual know what its like to be in a work environment while learning new things everyday as if we are in an outside school program. This job showed me how to teach others my knowledge by using simple techniques such as outreach activities to make people understand simple concepts also just teaching me what is and how to create an outreach program. I have learned all the steps educators take in creating lesson plans and understanding how the lesson benefits the participant so they walk away with a skill or knowledge. Now I can identify what it takes to teach others. This internship has also provided me with friendships and relationships that I would never had made without it. I have developed peer friendships by working and hanging out with each other on a daily basis. I have gained relationships with my supervisors, not just the worker to supervisor relationship but friendship as well. We are able to talk with each other not just about work, which has created a fun workplace. Finally this internship has given me connections that can benefit me for years to come in whatever field I decide to pursue. I feel it has given me everything it had to offer and it exceeded expectations in how amazing an experience this has been I gave the Adler my all and I hope I was able to return the favor.