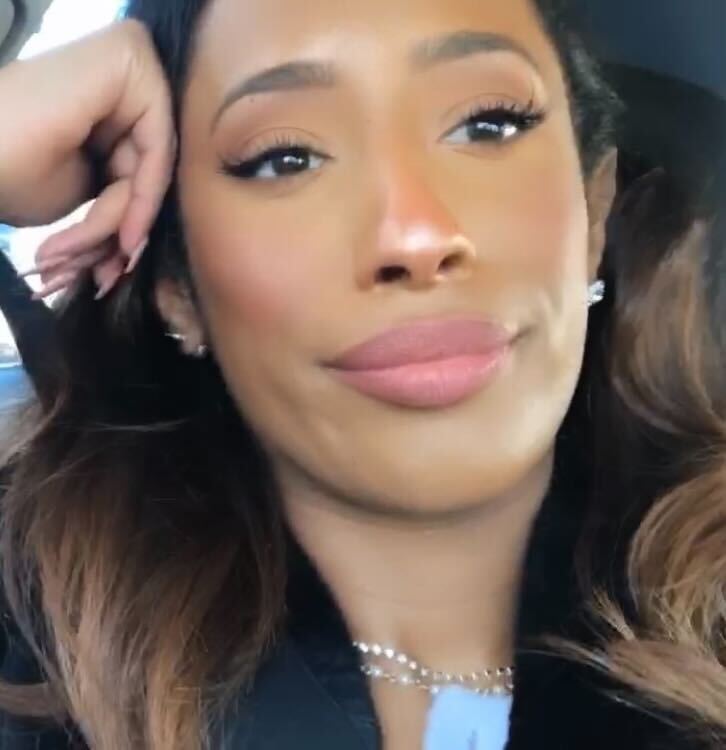

In this edition of Who’s who in the Zoo, meet Oluwatoyosi Oyegoke, a Zooniverse backend developer.

Who: Oluwatoyosi Oyegoke, Backend developer at Zooniverse

Location: University of Oxford

Zooniverse projects: Panoptes API, Panoptes Python Client & CLI, KaDE (Knowledge and Discovery Engine), BaJor (Azure Batch Job Runner), Active Learning Pipelines

What is your research about?

My work focuses on helping scientists manage the huge amount of data created by Zooniverse projects. These projects can produce millions of images from telescopes, wildlife cameras, or research surveys. Volunteers classify these images, and I build the systems that collect this information and make it useful for researchers.

I work on the Panoptes API, which is the core platform that stores project data and volunteer classifications. I also improve the Python client and CLI so researchers can easily access and analyse their data. Another part of my role involves building and maintaining the machine learning pipelines. These pipelines take the volunteer classifications, train models, run predictions, and manage large Azure Batch jobs.

In simple terms: scientists and volunteers create the data, machine learning tries to learn from it, and I build the tools and backend systems that help everything work together smoothly. My work makes it easier for researchers to understand very large datasets by improving the platforms and workflows behind the scenes.

How do Zooniverse volunteers contribute to your research?

Zooniverse volunteers play a central role in how the whole platform functions. They create the classifications that flow through the systems I work on, and their input is what brings each project to life. When a project is created, volunteers are the ones who generate the data that the platform processes, stores, and makes available to researchers.

My work focuses on the core systems behind this experience. I help maintain and improve the Panoptes API, the tools researchers use to access data, and the pipelines that handle classification processing and machine learning.

Everything depends on volunteers contributing high-quality classifications, and their work is what keeps the entire platform active and meaningful. What I find exciting is seeing how thousands of people from around the world can come together and create data that supports real scientific discovery. My role is to make sure the systems behind that process are fast, reliable, and able to handle the huge amount of participation that Zooniverse projects receive.

While I do not work on individual research outputs, the systems I help build and maintain support all the scientific papers, datasets, and discoveries that come from Zooniverse projects. Without volunteers, and without the infrastructure behind them.

What’s a surprising or fun fact about your research field?

For me, one surprising thing is how global the participation is. A project can receive classifications from people in completely different parts of the world within the same minute. It amazes me how many people contribute to science from their sofa, their commute, or wherever they happen to be.

What first got you interested in research?

I love working on systems that have a direct impact, and the mix of technology, community, and science is what keeps it exciting.

What’s something people might not expect about your job or daily routine?

One thing people might not expect is how often small changes make a big impact. Sometimes a single line of code or a small optimisation can improve performance for millions of classifications. It’s a very technical role, but it’s also rewarding to know that quiet, invisible work can support so many people doing science together.

Outside of work, what do you enjoy doing?

Outside of work, I spend my weekends playing football with friends. I also spend a lot of time playing video games like FIFA and GTA. It’s my favourite way to unwind and switch off. I also enjoy watching documentaries, especially ones about historical events, and I love exploring new technologies just out of curiosity. It keeps things fun and gives me something new to learn all the time.

Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

I’d just like to say that being part of Zooniverse has shown me how powerful community-driven science can be. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps move real research forward. It’s a privilege to help build the systems that make that possible, and I’m excited to see what volunteers and researchers will discover next.