In our Who’s who in the Zoo blog series we introduce you to some of the people behind the Zooniverse.

In this edition, meet Dr Liz Dowthwaite, who is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Nottingham, and long-term Zooniverse research collaborator

– Helen

Name: Liz Dowthwaite

Location: University of Nottingham, UK

Tell us about your role within the team

I have been working with the Zooniverse off and on for about 3 years. I don’t have an official Zooniverse job title, I am a Senior Research Fellow in Trustworthy Autonomous Systems (https://www.tas.ac.uk) and Horizon Digital Economy Research (https://www.horizon.ac.uk/) at Nottingham, and am lucky enough to be able to spend some of that time working with the Zoo team. However, I have been called the ‘tame psychologist’! My work with the Zooniverse focuses on understanding how volunteer experiences can be enhanced to encourage continued participation and benefit the volunteer.

What did you do in your life before the Zooniverse?

Before working with the Zooniverse I was doing the same things I do now! I did BSc Psychology and an MA in The Body and Representation at the University of Reading, UK. I also worked in the academic library there for 7 years as a library assistant receiving all the shiny new books. I did my PhD in Digital and Creative Economy at Nottingham, in the Horizon CDT, studing online webcomic communities. I started as a Research Assistant in Horizon in 2016 whilst writing up my PhD, moving on to Research Fellow when I graduated in 2018, and recently won a promotion to Senior Research Fellow.

What does your typical working day involve?

I am a research psychologist based in a computer science department, so I study how people interact with technology. I mostly work from home in a tiny village in Oxfordshire, being frequently interrupted by two cats who would swear they have never been fed in their lives. I travel up to Nottingham about once a month to see my PhD students, and also to teach postgrads about digital footprints, responsible research and innovation (RRI) and experimental design. In my day-to-day I work across a range of multidisciplinary projects, for example online moderation and end-to-end encryption, trust in technology among people with mental health difficulties, benchmarks for measuring trust, and online wellbeing. This involves a lot of online meetings with my colleagues around the country, and lots of time spent reading things on the internet! Some of this is managing and planning the projects, some is conducting research – I write and analyse a lot of questionnaires!

How would you describe the Zooniverse in one sentence?

The Zooniverse is a force for good in the online world, allowing anyone anywhere to make a real difference.

Tell us about the first Zooniverse project you were involved with

I tend to study the Zooniverse as a whole but I last year I worked with some of the team at Science Scribbler: Placenta Profiles to help them to understand more about their volunteers.

Of all the discoveries made possible by the Zooniverse, which for you has been the most notable?

I found a Supernova! Does that count?!

What’s been your most memorable Zooniverse experience?

When we run surveys with volunteers we often get some really lovely stories about what the Zooniverse really means to people, and I think that’s really wonderful. Our projects have connected people to their own histories and cultures, and made impacts on their current lives, which is really heartwarming and I love reading them.

What are your top three citizen science projects?

I don’t really have a favourite, I like to play with a range of projects. I tend to enjoy images and graphs the most. I was completely addicted to the original Muon Hunters, I saved all the images that looked like smiley faces, and it was really simple and quick and had a real ‘just one more’ vibe. I also love the University of Wyoming Raccoon Project because who doesn’t love trash pandas?

What advice would you give to a researcher considering creating a Zooniverse project?

Think about how you can support and engage with your volunteers beyond just asking them to take part in the project!

How can someone who’s never contributed to a citizen science project get started?

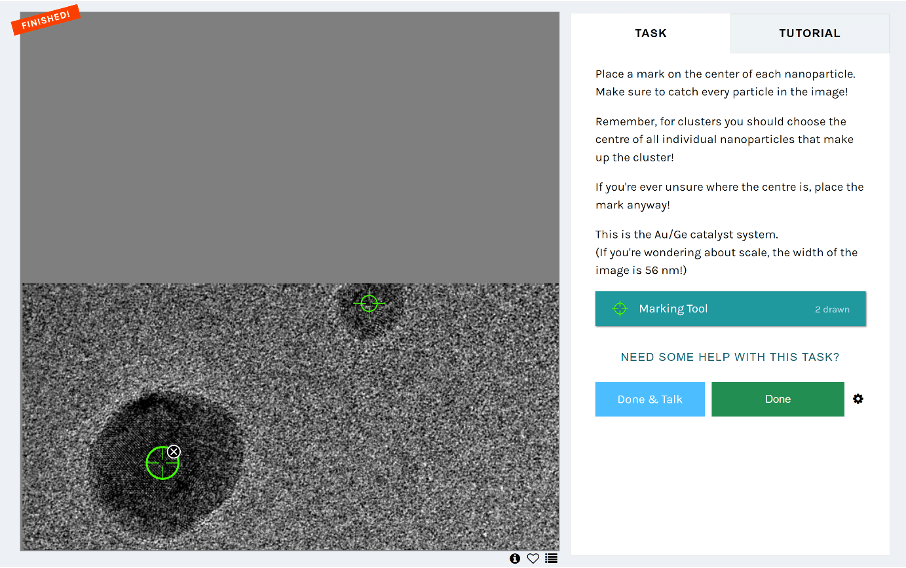

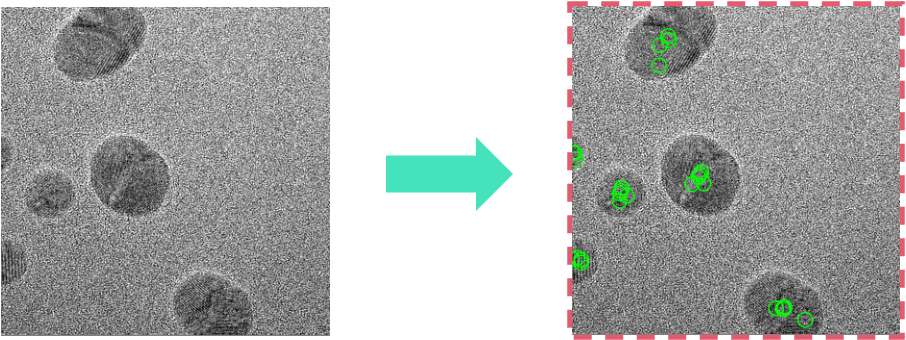

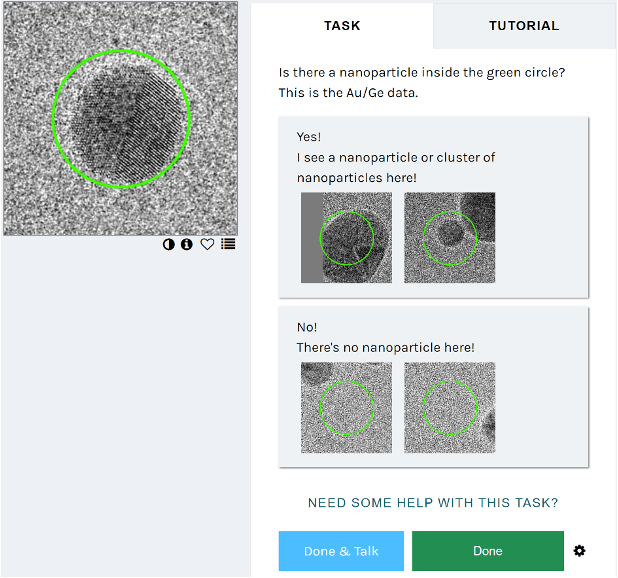

Just get clicking! There really is something to interest everyone on the Zooniverse – explore the project pages and dive in. Most of the projects have excellent tutorials to get you started. Remember that it’s ok to get things wrong, many people classifying the same things leads to an excellent consensus and high quality data. And if a project isn’t for you, there is bound to be another one out there that you’ll love.

When not at work, where are we most likely to find you?

On the internet! But also reading the London Review of Books, drinking wine, or walking in the beautiful countryside around Oxfordshire – sometimes all of those at once if we find an awesome country pub! I’m also a keen cook (but not baker) and an extremely keen eater, and a reluctant runner (partly due to all of the eating)…

You can hear more from Liz on Twitter or on her blog.