One of the best things about being an educator on the Zooniverse development team is the opportunity to interact with teachers who are using Zooniverse projects in their classroom and teachers who are interested in using Zooniverse projects in the classroom. Teachers cite several reasons about why they use these projects – Authentic data? Check. Contributing to cutting-edge research across a variety of scientific fields? Check. Free? Check. Classifying a few galaxies in Galaxy Zoo or identifying and measuring some plankton in Plankton Portal can be an exciting introduction to participating in scientific investigations with “the professionals.” This isn’t enough though; teachers and other educators are hungry for ways to facilitate deeper student engagement with scientific data. Zooniverse educators and developers are consistently asked “How can my students dig deeper into the data on Zooniverse?”

This is where ZooTools comes into play. The Zooniverse development team has recently created ZooTools as a place where volunteers can observe, collect, and analyze data from Zooniverse citizen science projects. These tools were initially conceived as a toolkit for adult volunteers to use to make discoveries within Zooniverse data but it is becoming apparent that these would also have useful applications in formal education settings. It’s worth pointing out that these tools are currently in beta. In the world of web development beta basically means “it ain’t perfect yet.” ZooTools is not polished and perfect; in fact it’s possible you may encounter some bugs.

Projects like Galaxy Zoo and Planet Hunters have an impressive history of “extra credit” discoveries made by volunteers. Galaxy Zoo volunteers have made major contributions to the astronomy literature through the discovery of the green peas galaxies and Hanny’s Voorwerp . In Planet Hunters volunteers use Talk to share methods of exploring and results from the project’s light curves. ZooTools lowers the barrier of entry by equipping volunteers with some simple tools to look for interesting relationships and results contained within the data. No specialist knowledge required.

We’ve only begun thinking about how ZooTools could be used in the classroom. I started my own investigation with a question that came from a Zooniverse classroom visit from last spring. While making observations as a class about some of the amazing animals in Snapshot Serengeti one young man asked about civets. He wanted to know If they were nocturnal. We had an interesting discussion about how you could find out this information. The general consensus was to Google it or look it up on Wikipedia. I wondered if you could use the data contained within Snapshot Serengeti to come up with a reasonable answer. I was excited to roll-up my sleeves and figure out how to use these tools to find a likely answer. Here are the steps I took…

Step 1: Log-in to Zooniverse and go to ZooTools.

Step 2: Select a project. Currently only have a few projects have data available to explore using ZooTools.

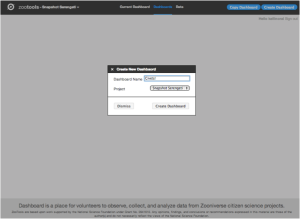

Step 3: Create a dashboard.

Step 4: Name your dashboard something awesome. I called mine Civets! for obvious reasons.

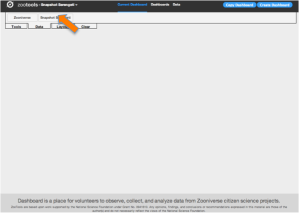

Step 5: This is your blank dashboard.

Step 6: It’s time to select a data source. I selected Snapshot Serengeti.

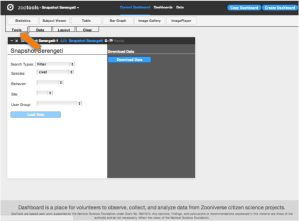

Step 7: This is the data source.

Step 8: I wanted to be able to filter my data so I selected Filter under search type. The name of this dataset in Snapshot Serengeti 1.

Step 9: Since I wanted to look at civets, I selected that on the species dropdown menu and then clicked Load Data. My dataset will only contain images that Snapshot Serengeti volunteers identified as civets.

Step 10: I had my data; next it was time to select a Tool. I selected Tools at the top of the page.

Step 11: I selected Subject Viewer because this tool allows my to flip through different images.

Step 12: Next I had to connect my data source to my tool. From the Data Source drop down menu I selected Snapshot Serengeti 1.

Step 13: In order to get a good luck at the images in my dataset I clicked the icon shaped like a fork to close the pane. I then used the arrows to advance through the images.

I flipped through the images and kept track of the night versus day. Of the 37 images in my dataset, I observed that 34 were taken at night and 3 were taken during the day. This led me to the conclusion that civets are likely nocturnal. This was so much more satisfying than just going to Google or Wikipedia. A couple of other questions that I explored…

What is the distribution of animals identified at one camera trap site?

How many honeybadgers have been observed by Snapshot Serengeti volunteers across different camera traps?

Of course this is just the tip of the iceberg. Currently you can explore Galaxy Zoo, Space Warps, and Snapshot Serengeti data using ZooTools. Currently you can use ZooTools to explore data from Galaxy Zoo, Space Warps, and Snapshot Serengeti. The specific tools and datasets available vary from project to project. In Galaxy Zoo for example you can look at data from Galaxy Zoo classifications or from SDSS Skyserver. Hopefully you’ll be inspired to have a play with these tools! What questions would you or your students like to explore?